This article was originally published on Newsroom on 19 May 2021.

First off, and in case you’d forgotten, Covid-19 is a highly transmissible infectious disease – once someone has it, they could quickly give it to many others. Contact tracing helps find all the people an infectious person has interacted with and isolate them so they can’t spread the disease further. When public health officials go through this process for other diseases, it can take days or weeks. With Covid-19, time is of the essence because every day we leave the virus in the community, more people could become infected. People might be infectious before they show symptoms too, which makes acting quickly even more important. So, we can use digital technology to speed things up and help public health officials have confidence that they’ve found all potentially infectious people.

What does the NZ app do?

Features of the NZ COVID Tracer app grow each month with new releases, but the following are key:

First off, and in case you’d forgotten, Covid-19 is a highly transmissible infectious disease – once someone has it, they could quickly give it to many others. Contact tracing helps find all the people an infectious person has interacted with and isolate them so they can’t spread the disease further. When public health officials go through this process for other diseases, it can take days or weeks. With Covid-19, time is of the essence because every day we leave the virus in the community, more people could become infected. People might be infectious before they show symptoms too, which makes acting quickly even more important. So, we can use digital technology to speed things up and help public health officials have confidence that they’ve found all potentially infectious people.

What does the NZ app do?

Features of the NZ COVID Tracer app grow each month with new releases, but the following are key:

- Provide up-to-date contact details so Ministry of Health can call you if they need to for contact tracing

- Scan QR codes or enter details manually to keep a digital diary of where you have been

- Automatically log Bluetooth devices you have been near

- Be notified if your records overlap with people who have tested positive so you can get tested and isolate to cut off the chains of transmission

So, this means instead of going through a big central database to find potentially infected people, the Ministry of Health pushes out data about active cases in a secure way, so the app can check for matches on the phone itself. This 'decentralised' approach has become the predominant design choice in digital contact tracing systems around the world.

While many other governments tried a centralised approach first, most quickly abandoned it when people were rightfully concerned about privacy (for example, in Germany, the UK, and Norway).

Interestingly, when most countries went Bluetooth-first, New Zealand picked a QR code approach. We were pretty late to adopt Bluetooth – it was only added in December 2020. A number of other jurisdictions started with Bluetooth and then added QR code scanning too, including in Singapore, Sri Lanka, and states in Australia. Both have pros and cons but having them working together is likely better than either alone.

Did people use the app?

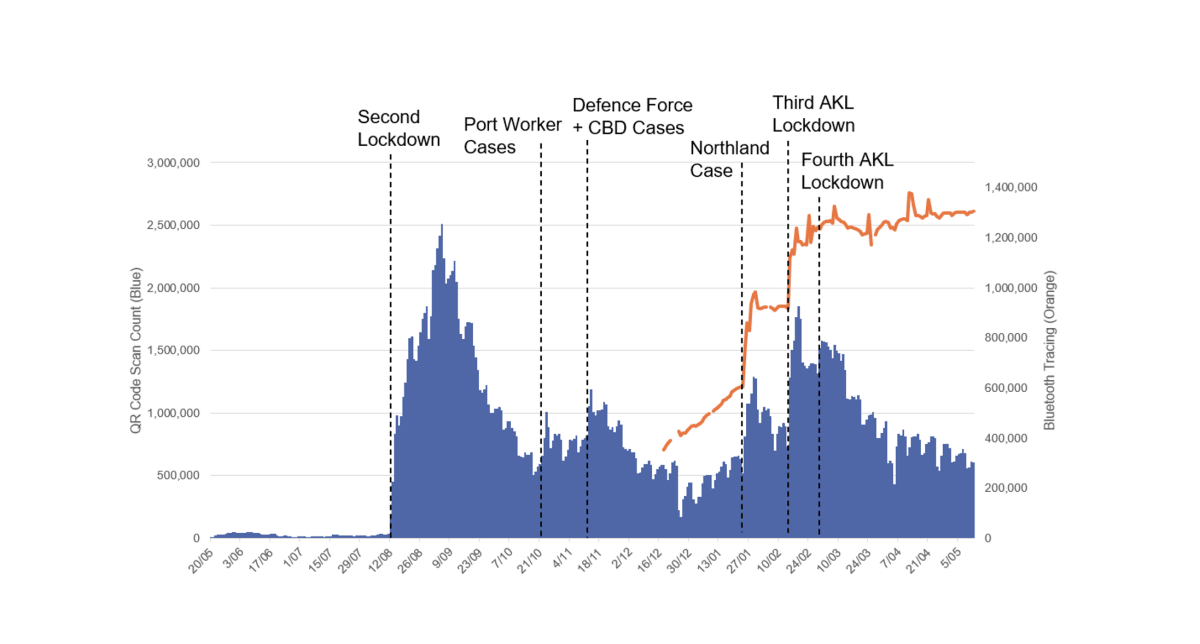

The Ministry of Health regularly releases data about app usage. There are now about 2.8 million people registered (which could include a small number of duplicates). In early September 2020, we reached 2.5 million QR code scans in one day, from almost a million phones. The daily scan rate has fluctuated since then, but numbers participating in Bluetooth Tracing stays strong when the QR code scan rate falls - there are now 1.35 million devices exchanging Bluetooth handshakes around the country.

Overall, data shows Kiwis are strongly driven by perception of risk. When new cases appeared in the community, people acted by scanning in and turning Bluetooth Tracing on. As the perception of risk lowered and alert levels decreased, participation dropped significantly. Updates to the app such as gamification and improving compatibility with older devices don’t get participation rates up as much as new cases.

The problem with this approach is when someone tests positive, health officials need their records from before that test, and you need your records so that you can find out if there are any overlaps - starting to scan at that point is too late. To be useful, people need seven-14 days of records. Modelling of how effective digital contact tracing might be suggests a 60-80 percent participation rate is necessary (in theory) before we can be confident data collected will be helpful for containing any possible outbreak. We’ve never reached that rate - only about 35 percent of the adult population actively participate in Bluetooth Tracing now.

Has the app worked?

It’s really hard to say in a country with relatively few cases. Digital contact tracing is just one tool in the epidemiology toolbox – most credit for New Zealand’s mostly Covid-free status must go to restricting movement through lockdowns and border controls. Since people started using the app properly during the second wave in August/September 2020, we haven’t had the kind of outbreak digital contact tracing should be able to help with - and we hope we never do.

Overseas, the evidence is mixed. Not many countries have sufficiently high numbers participating in digital contact tracing. These systems are helping notify potentially exposed contacts more quickly, but they tend to rely on people doing the right thing when notified. There are real questions about whether these digital systems are much better or faster than manual contact tracing, and we’ll need to look back on the data in years to come to work that out.

But we do have some local evidence that the app can be helpful. In January 2021, when a person tested positive in Northland, the fact they had used NZ COVID Tracer regularly meant health authorities had more information to work with, and more confidence that risk of the disease spreading further was relatively low. Contrast that to the Valentine’s Day cases a month later, and in retrospect we might have avoided a snap regional lockdown.

What have we learned?

Although the Tracer app was released in May 2020, hardly anyone used it for the first three months. This was mostly because it wasn’t mandatory for businesses to display the government QR code and because there were multiple QR codes for different systems made by private-sector providers. Data was spread across multiple tools and platforms (known as fragmentation) that didn’t link to a greater whole. We learnt from this that in an emergency, the government must show leadership and co-ordinate the response, so everyone is working towards a common goal collaboratively.

This takes us to the CovidCard saga - a proposal for all New Zealanders to be issued with a Bluetooth-enabled card that would keep records of interactions. Media coverage at the time was confusing - was this a private-sector project led by Sam Morgan, or a government project owned by the Department of Internal Affairs? There were certainly influencers promoting the card as the solution to Covid-19, a technology that would end lockdowns and open the borders.

But the Government was cautious, running focus groups and surveys, trialling the card in hospitals, MIQ facilities and a community in Rotorua. This approach was well-justified, because the card was predicted to cost $100m over two years (others estimated $300m-400m over the same period), so the Government needed confidence it would work. In the end, trials showed the cards were about as effective as Bluetooth Tracing in the app. Most of the issues were ‘human’, such as people remembering to wear the cards or wear them correctly. If the Government had gone ahead with the proposal at an early stage, we could have spent a lot of money on a system not much better than the app, which only cost a few million dollars.

We’ve also learnt the value of international co-operation and open sourcing code for everyone to share. For example, NZ’s Bluetooth system is largely based on Ireland’s version; England’s QR code scanning is largely based on ours; NZ COVID Tracer was adapted for an app recently released in the Cook Islands. During a pandemic, it’s important everyone pitches in and works together, and digital contact tracing has been one area where sharing has led to good outcomes. What if we could do this with other public sector technologies? For example, if governments shared tools for managing public consultation, could people around the world make their voices heard more effectively?

A missed opportunity?

Once the initial app was released, ongoing development was relatively slow - it felt like features such as manual entries and Bluetooth Tracing, and decisions to build confidence through making the code open-source, took a long time compared to the pace of the pandemic. But that is in part because New Zealand’s experience of Covid-19 has meant we’ve had time to think, to watch others around the world and learn, rather than constantly responding to an ever-worsening situation. This has meant most of our improvements have been incremental, rather than ground-breaking, because we are already in a fortunate position.

However, introduction of digital contact tracing could have been an opportunity for the government to take real action to address an ongoing issue in New Zealand - digital inclusion. While the magnitude of the problem is difficult to measure accurately, as much as 20 percent of the adult population may not have regular access to digital technology. Even those who own smartphones or have access to the internet may lack the skills or trust to use them effectively.

We could have taken a more inclusive approach to digital contact tracing by ensuring every person who wanted to participate could do so fully. If the government had allocated resources towards policies like smartphone vouchers, further subsidies for internet and data costs, and broader technical skills training and support programmes, we could have really moved the needle on digital inclusion. This would have had a long-lasting impact well beyond the pandemic, helping people access government and banking services conveniently, improving educational and economic opportunity, and keeping in touch more easily. For now, as many of us as possible need to keep scanning in, so that we have a hope of a more digitally inclusive future.

The problem with this approach is when someone tests positive, health officials need their records from before that test, and you need your records so that you can find out if there are any overlaps - starting to scan at that point is too late. To be useful, people need seven-14 days of records. Modelling of how effective digital contact tracing might be suggests a 60-80 percent participation rate is necessary (in theory) before we can be confident data collected will be helpful for containing any possible outbreak. We’ve never reached that rate - only about 35 percent of the adult population actively participate in Bluetooth Tracing now.

Has the app worked?

It’s really hard to say in a country with relatively few cases. Digital contact tracing is just one tool in the epidemiology toolbox – most credit for New Zealand’s mostly Covid-free status must go to restricting movement through lockdowns and border controls. Since people started using the app properly during the second wave in August/September 2020, we haven’t had the kind of outbreak digital contact tracing should be able to help with - and we hope we never do.

Overseas, the evidence is mixed. Not many countries have sufficiently high numbers participating in digital contact tracing. These systems are helping notify potentially exposed contacts more quickly, but they tend to rely on people doing the right thing when notified. There are real questions about whether these digital systems are much better or faster than manual contact tracing, and we’ll need to look back on the data in years to come to work that out.

But we do have some local evidence that the app can be helpful. In January 2021, when a person tested positive in Northland, the fact they had used NZ COVID Tracer regularly meant health authorities had more information to work with, and more confidence that risk of the disease spreading further was relatively low. Contrast that to the Valentine’s Day cases a month later, and in retrospect we might have avoided a snap regional lockdown.

What have we learned?

Although the Tracer app was released in May 2020, hardly anyone used it for the first three months. This was mostly because it wasn’t mandatory for businesses to display the government QR code and because there were multiple QR codes for different systems made by private-sector providers. Data was spread across multiple tools and platforms (known as fragmentation) that didn’t link to a greater whole. We learnt from this that in an emergency, the government must show leadership and co-ordinate the response, so everyone is working towards a common goal collaboratively.

This takes us to the CovidCard saga - a proposal for all New Zealanders to be issued with a Bluetooth-enabled card that would keep records of interactions. Media coverage at the time was confusing - was this a private-sector project led by Sam Morgan, or a government project owned by the Department of Internal Affairs? There were certainly influencers promoting the card as the solution to Covid-19, a technology that would end lockdowns and open the borders.

But the Government was cautious, running focus groups and surveys, trialling the card in hospitals, MIQ facilities and a community in Rotorua. This approach was well-justified, because the card was predicted to cost $100m over two years (others estimated $300m-400m over the same period), so the Government needed confidence it would work. In the end, trials showed the cards were about as effective as Bluetooth Tracing in the app. Most of the issues were ‘human’, such as people remembering to wear the cards or wear them correctly. If the Government had gone ahead with the proposal at an early stage, we could have spent a lot of money on a system not much better than the app, which only cost a few million dollars.

We’ve also learnt the value of international co-operation and open sourcing code for everyone to share. For example, NZ’s Bluetooth system is largely based on Ireland’s version; England’s QR code scanning is largely based on ours; NZ COVID Tracer was adapted for an app recently released in the Cook Islands. During a pandemic, it’s important everyone pitches in and works together, and digital contact tracing has been one area where sharing has led to good outcomes. What if we could do this with other public sector technologies? For example, if governments shared tools for managing public consultation, could people around the world make their voices heard more effectively?

A missed opportunity?

Once the initial app was released, ongoing development was relatively slow - it felt like features such as manual entries and Bluetooth Tracing, and decisions to build confidence through making the code open-source, took a long time compared to the pace of the pandemic. But that is in part because New Zealand’s experience of Covid-19 has meant we’ve had time to think, to watch others around the world and learn, rather than constantly responding to an ever-worsening situation. This has meant most of our improvements have been incremental, rather than ground-breaking, because we are already in a fortunate position.

However, introduction of digital contact tracing could have been an opportunity for the government to take real action to address an ongoing issue in New Zealand - digital inclusion. While the magnitude of the problem is difficult to measure accurately, as much as 20 percent of the adult population may not have regular access to digital technology. Even those who own smartphones or have access to the internet may lack the skills or trust to use them effectively.

We could have taken a more inclusive approach to digital contact tracing by ensuring every person who wanted to participate could do so fully. If the government had allocated resources towards policies like smartphone vouchers, further subsidies for internet and data costs, and broader technical skills training and support programmes, we could have really moved the needle on digital inclusion. This would have had a long-lasting impact well beyond the pandemic, helping people access government and banking services conveniently, improving educational and economic opportunity, and keeping in touch more easily. For now, as many of us as possible need to keep scanning in, so that we have a hope of a more digitally inclusive future.